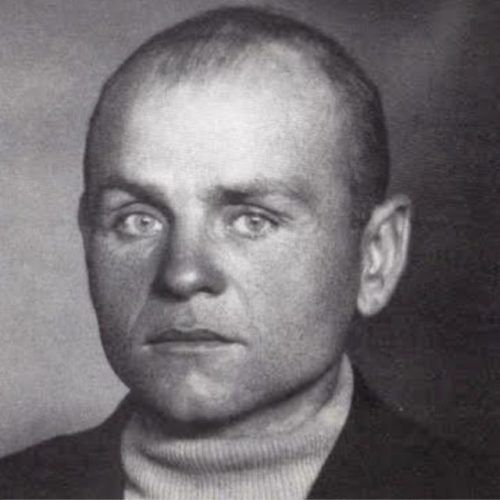

Leopold “Poldek” Socha was a mild-mannered maintenance man who saved the lives of eleven Jews by hiding them in the underground sewers of Lvov, Poland during the Nazi occupation.

An uneducated Pole living in poverty, the only job Poldek could get was cleaning up the underground sewage system in Lvov. The pay was so low that he supplemented his income with theft and burglary.

The Germans occupied Lvov in 1941 and immediately forced all of the city’s Jews into a squalid, overcrowded ghetto teeming with disease, death and misery. Ignorant and barely literate, Poldek had something more valuable than education, something the oh-so-sophisticated Nazi leaders lacked: a moral compass. Outraged by the Nazi occupiers’ persecution of the Jews of Lvov, Poldek – who didn’t know any Jews personally – decided to do something about the injustice he witnessed. He visited the Jewish ghetto and after befriending some of its desperate occupants, he vowed to find a way to rescue Jews. He had no money, resources, or influence; all this humble man had was a desire to save the lives of complete strangers. Poldek convinced a fellow sewer-worker, Stefan Wroblewski, to help carry out his brave mission, although they still weren’t sure exactly how they’d accomplish it.

The aspiring heroes got their answer when the Nazis began the Aktion, liquidation of the ghetto, which meant transporting the inhabitants to concentration and death camps. The night the Aktion started, in June 1943, Poldek was cleaning out sewage canals when he saw a family of Jews trudging through the stinking filth, heading toward the river. They had escaped the ghetto through the floorboards. Knowing that the riverbank was crowded with police and Gestapo storm troopers, Poldek approached the terrified Jews and told them not to go that way. Instead, he said, they should stay underground and he would take care of them.

Poldek brought the Jews food and clean clothing. Others found out about the safe hiding place and joined them until there were twenty people living in the sewer. Poldek, his wife Magdalena, and Stefan and his wife took care of all the hidden Jews’ needs. At the beginning, the Jews paid them, but their money soon ran out and the brave Polish couples continued paying for everything from their own meager paychecks.

Hiding in the sewers was a temporary way to stay alive, but it was horrible. It was dark, cold, wet, and the fetid smell was overpowering. There was nothing to see or do, and the sheer terror of being discovered never left them. One of the Jews, eight months pregnant, was there with her elderly grandmother. The conditions were so harsh and unsanitary that both the baby and the grandmother died. The Sochas and the Wroblewskis went to great trouble to remove the bodies from the sewer in the dead of night, and bury the tiny infant and his aged great-grandmother. Other Jews couldn’t take the brutal conditions in the sewer and they decided to find another safe haven, but getting out of the sewer was fraught with danger and they died on the way out. When he found their bodies, Poldek made sure they received burials.

Besides providing the hidden Jews with food, medicine, clothing, blankets and other necessities of life, Poldek went out of his way to enable them to practice their faith. He rummaged through empty tenements in the ghetto – the residents had been sent to concentration camps – until he found a dog-eared prayer book. During Passover, when the Jews couldn’t eat bread, he brought them potatoes.

Among the Jews hiding in the sewers was the Chirowski family of four. The Chirowski children were 4 and 7 years old. It was very difficult to keep the children occupied and entertained for over a year in their filthy, smelly underground hiding place. Mother Paulina Chirowski spent the days telling her children colorful stories and keeping up their schooling as much as she could. In Paulina’s testimony to Yad Vashem years later, she recalled that much of the family’s time was spent huddling under the sewer grills and listening to street noise, their only link with the normal world above. One particular painful moment among many she mentioned in her testimony was when she and her little daughter overheard a mother and daughter above chatting happily about which flowers to get on their way to church. The child was distraught, not understanding why a different little girl and her mommy were able to live freely and enjoy life when she was stuck living in literal excrement day after day. To soothe the girl, Paulina promised her that they too would be free one day – although she wasn’t sure if she believed it.

Finally, after the Jews had been underground for thirteen months, Lvov was liberated by the Russians and it was safe to come out of the sewers. Of the 21 Jews who found refuge in the sewers, 10 survived, including the entire Chirowski family.

The war ended in 1945, and the next year Poldek and his daughter were on their bicycles when a freak tragedy occurred. An out-of-control Soviet military truck careened towards them. Thinking quickly, Poldek used his bicycle to push his daughter out of the way, saving her life but sacrificing his own. He was only 36 years old.

Poldek Socha and his wife Magdalena were honored by Israeli Holocaust Memorial Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations in 1978. Three years later, the Wroblewskis were also honored.

In 2011 Poldek Socha was the subject of the movie “In Darkness,” a drama by acclaimed director Agnieszka Holland, which was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

For saving eleven Jews, at great risk to themselves, we honor the Sochas and the Wroblewskis as this week’s Thursday Heroes.

With thanks to Yad Vashem

Get the best of Accidental Talmudist in your inbox: sign up for our weekly newsletter.