Long before our modern era of global travel and instant communication, two intrepid Jewish adventurers, both named Benjamin, visited the farthest corners of the Jewish world and wrote vivid accounts of what they saw. These travel books – written seven hundred years apart – provide our most accurate look at Jewish life in earlier times.

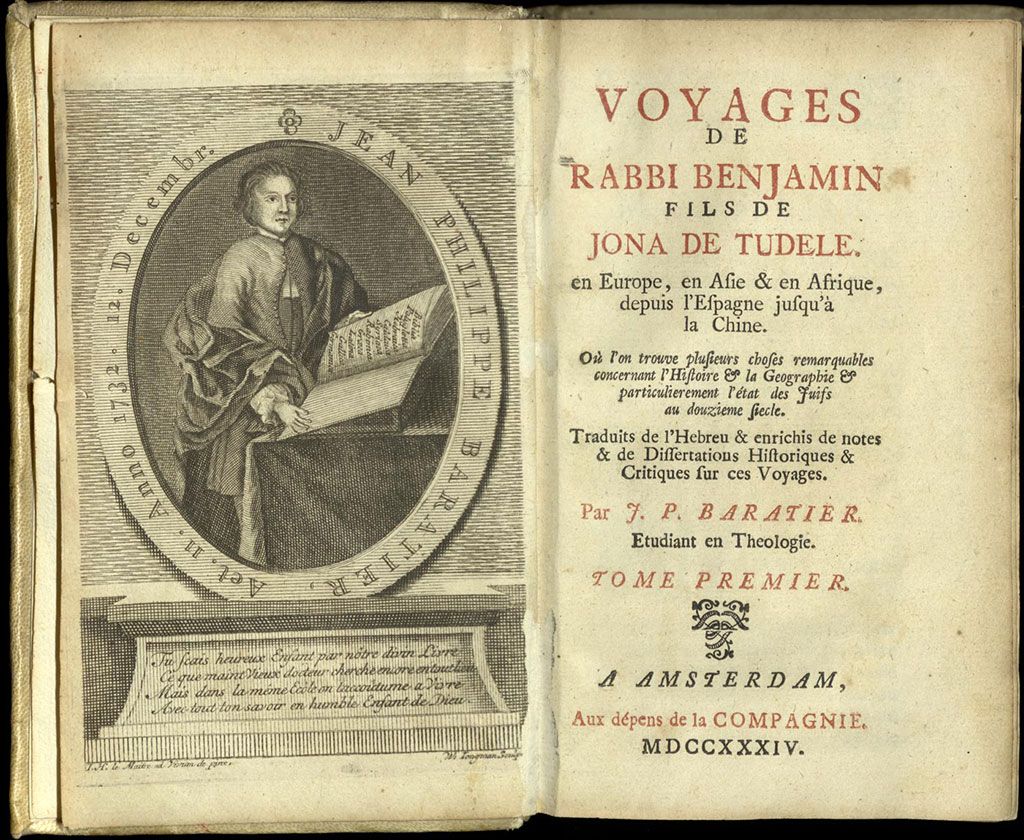

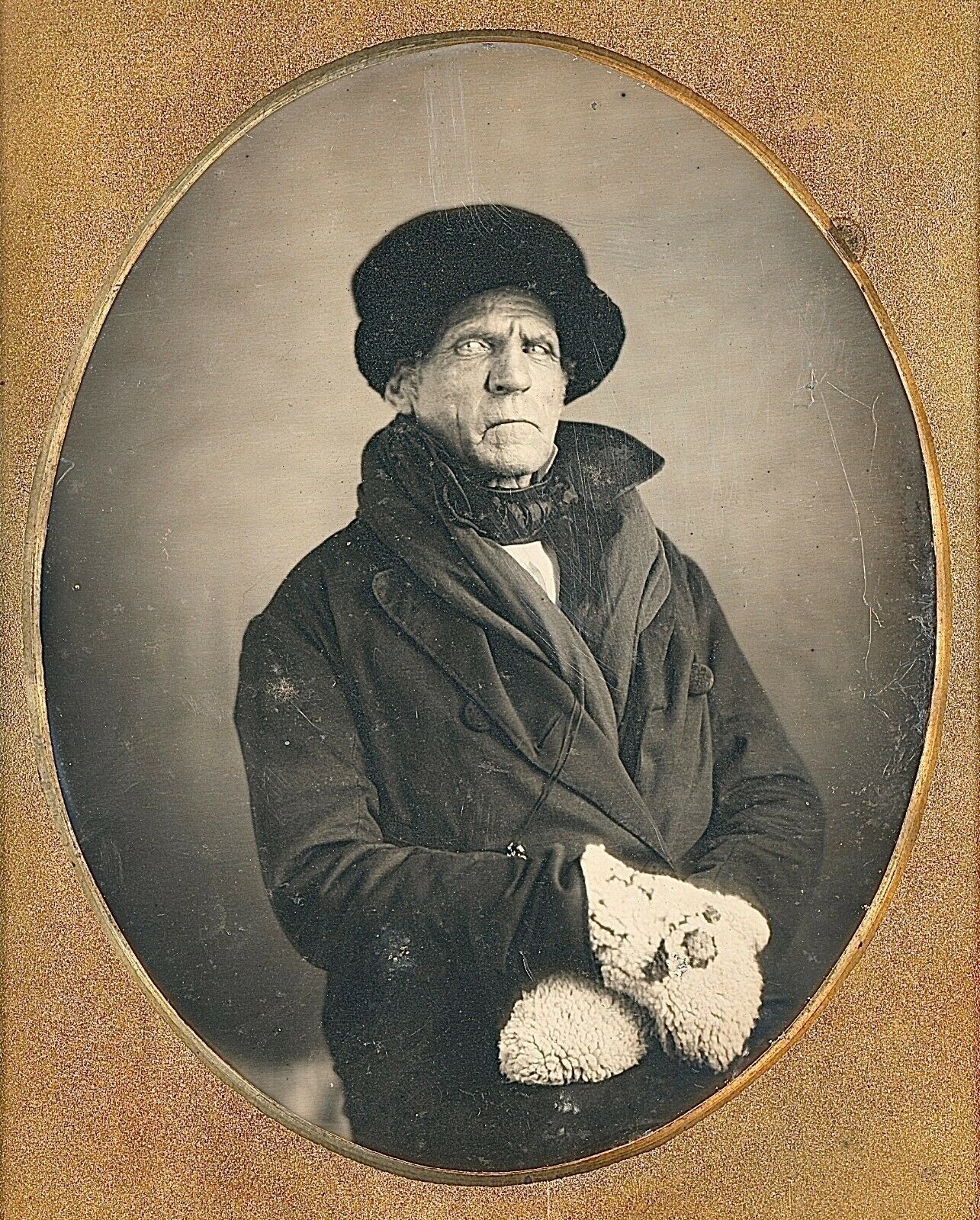

Benjamin of Tudela was a Spanish rabbi and traveler who chronicled his journeys throughout Europe, Asia and Africa in the 12th century. He was one of the first from Western Europe to visit Asia, 100 years before Marco Polo’s famous travels. Benjamin’s writings are an important source of historical information about everyday life and commerce in medieval times.

Benjamin was born in Tudela, now part of Spain but at the time in the Kingdom of Navarre. The territory had recently been conquered by Christians after being under Muslim rule for three hundred years. The area was cosmopolitan and diverse, and Benjamin spoke several languages.

Not much is known about Benjamin’s early life, or what motivated his travels. Repeated mentions of the coral trade in his writings suggest he may have been a gem merchant. He traveled to many Jewish communities in far-flung places and reported extensively about them. Perhaps he was creating a guide for Jewish travelers fleeing oppression or going on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. During his wide-ranging travels, whenever he found a Jewish community he stopped and spent time getting to know the locals and writing detailed accounts of their lives, customs, work and religious practice. He recorded the population count and names of prominent scholars and community leaders. Through Benjamin we learn of Jewish occupations in different places, for instance the silk-weavers in Thebes, dyers in Brindisi, tanners in Constantinople, glass-makers in Aleppo and Tyre. He interviewed poor Jewish workmen, humble Jewish peasants, and wealthy Jewish shipowners.

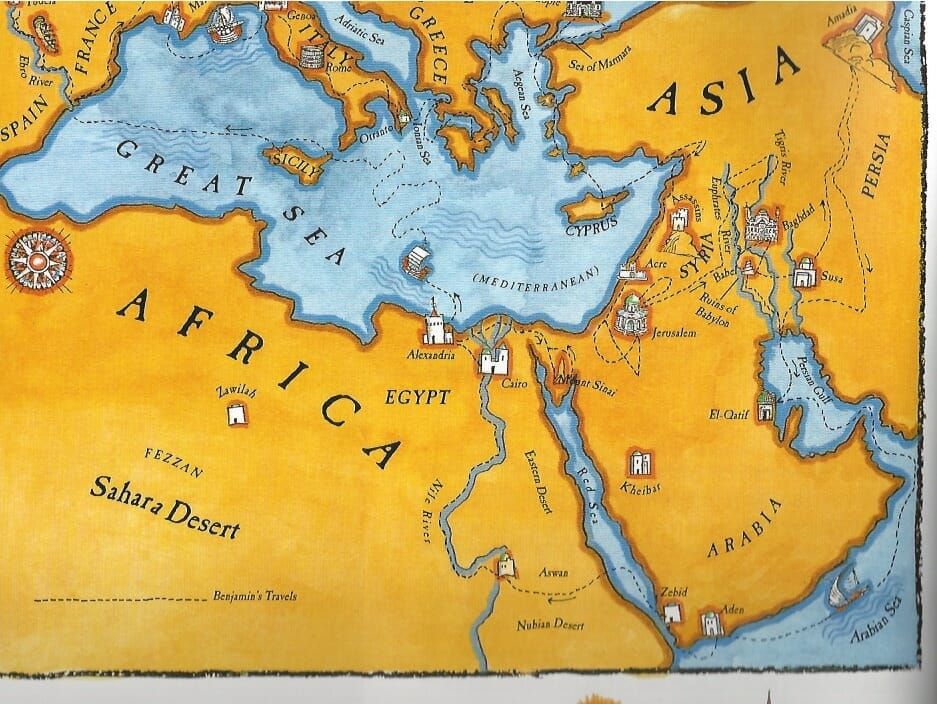

Benjamin left home sometime between 1159 and 1163, traveling first to Zaragoza and then throughout Spain and France before boarding a sailing ship at Marseilles and visiting Italy. He spent several weeks in Rome, during which he described its world-famous art and antiquities, as well as the local Jewish community’s difficult relationship with Pope Alexander III. Throughout his travels, as he collected information he made sure to thoroughly research everything to make sure he had the fact, and always cited sources. He traveled through Greece and reached Constantinople, where he stayed for a period and described Jewish and non-Jewish communities.

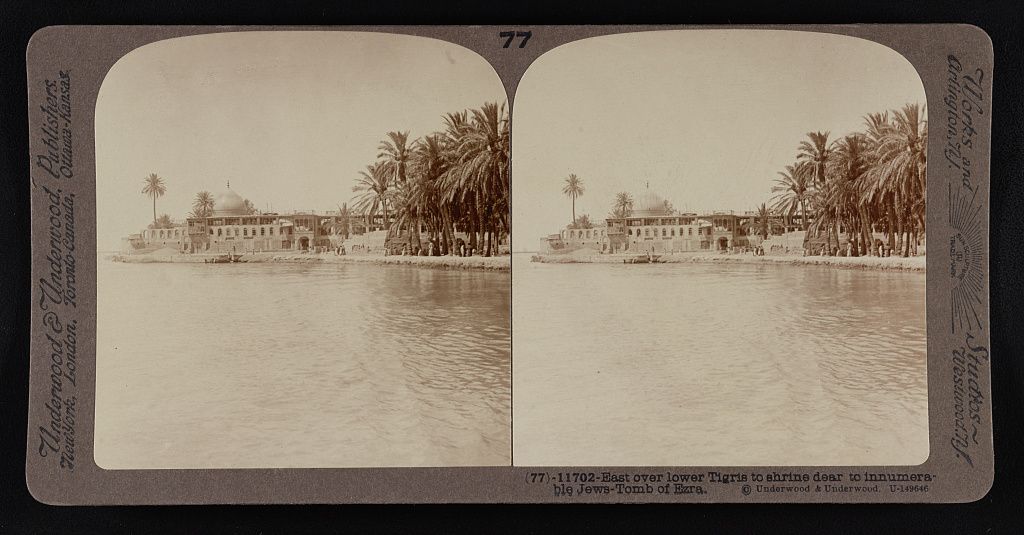

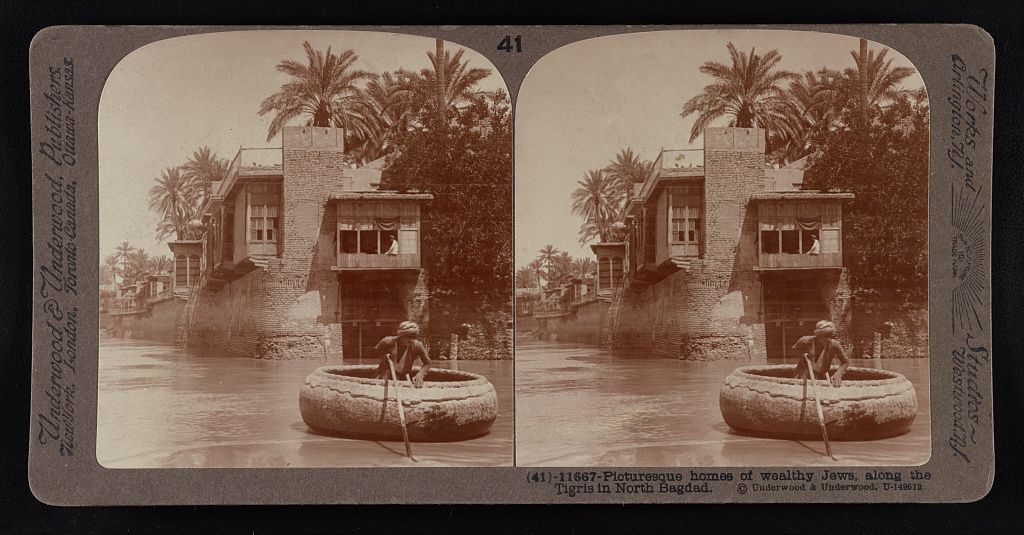

Wherever he went, he recorded vivid accounts of those he met and their lives, sharing shrewd insights about places and people. After traveling through modern-day Turkey he went to the Middle East, visiting Lebanon and Syria before reaching Jerusalem, a land dear to his heart. After visiting the Holy Land, Benjamin made his way through Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) to Baghdad and Ezra’s Tomb, and then back across the Arabian peninsula to North Africa and Egypt, where he spent an extended stay. Finally, he visited Ethiopia, and was one of the first to describe the Jewish community there, which was completely cut off from the rest of the Jewish world. Benjamin returned home to Tudela in 1173, more than ten years after leaving.

Benjamin of Tudela published a book in Hebrew about his adventures called The Travels of Benjamin which provides vivid descriptions of over 300 cities and many locations famous from the Bible. Throughout his writings, a recurring theme is his respect for Islam, especially the leaders of the Caliphate, who did great charitable works. He describes a world where Jews and Muslims lived largely in harmony, oftentimes occupying the same neighborhoods and conducting business together. Benjamin’s book was popular with readers, both Jewish and non-Jewish, and a map of his itinerary has been an indispensable resource for historians for centuries. The book has been translated into virtually every European language and is still studied today.

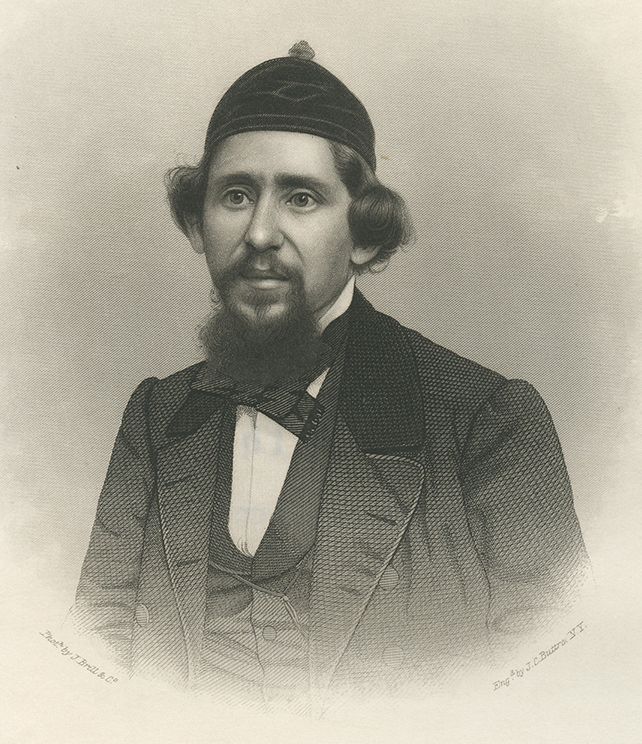

The second traveling Benjamin was Israel Joseph “JJ” Benjamin, a Jewish-Romanian historian and writer who took the pen name Benjamin II in homage to Benjamin of Tudela.

JJ was born in 1818 and found early success in the Moldavian lumber business. However, in his mid-20’s the business failed and he lost everything. Instead of doing what most would have done – getting a job or starting a new business – JJ decided to indulge his thirst for adventure, in a big way. He would find the 10 Lost Tribes of Israel.

The possible existence of lost tribes of Jews was an enduring mystery. In Biblical times, Israelites were divided into 12 tribes, each inheriting land in Israel. (The tribe of Levi did not own land.) After the death of King Solomon around 922 BCE, Israel split into two kingdoms, northern and southern. The northern kingdom was conquered 200 years later, and the ten tribes who lived there assimilated into other cultures. The southern kingdom, composed of the tribes of Judah, Simeon and part of Benjamin, was conquered by the Babylonians in 586 BCE and the Jews were exiled to Babylon (modern-day Iraq.) Many of them assimilated but others remained Jews, eventually returning to Jerusalem and building the Second Temple.

Today’s Jews are mostly descended from the tribe of Judah. Rumors have persisted over the years that the tribes of the northern kingdom didn’t completely disappear and that remnants remain, still practicing Jewish traditions although far removed from other Jewish communities.

In his quest to prove the rumors true, JJ started in Vienna in January 1845 and then traveled to Constantinople before visiting towns around the Mediterranean Sea. Two years later he reached Egypt, and then Jerusalem. For the next three years JJ traveled through the Middle East, including Babylonia, Syria, Persia, and Kabul. Next he visited Italy, Algeria and Morocco.

JJ finished the trip in France in 1852, where he wrote a book called “Five Years in the Orient.” It was published in Hebrew and French, and an expanded version, “Eight Years in Asia and Africa” was published in German and English.

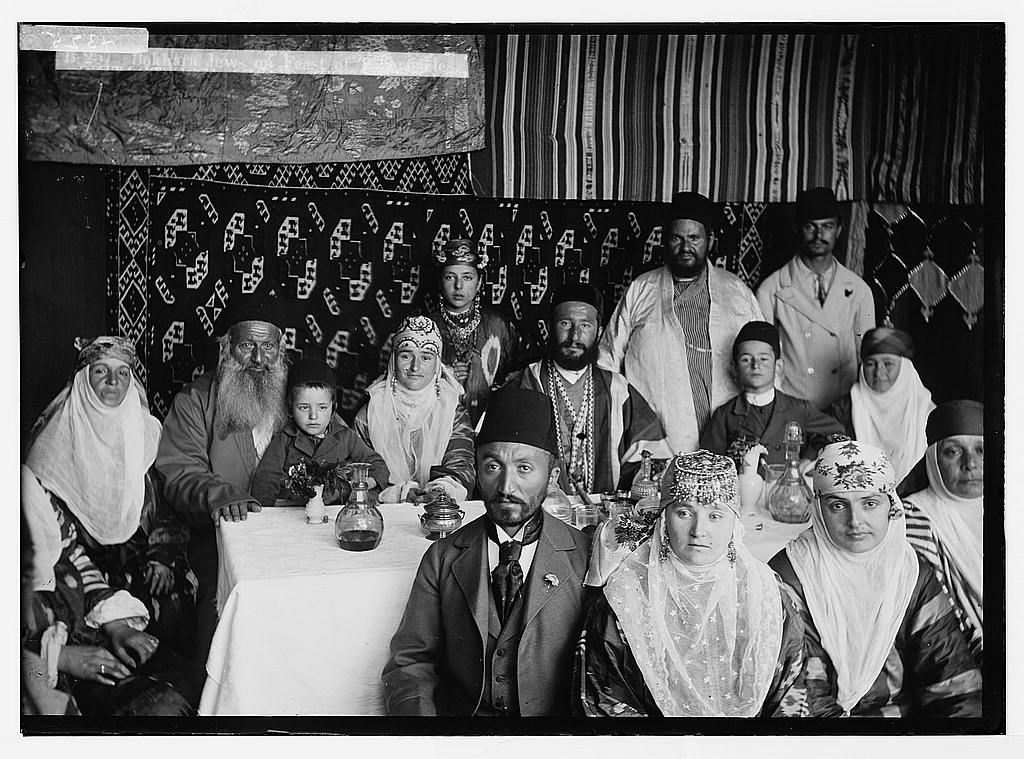

During his extensive journey through Asia and north Africa, JJ visited many Jewish communities, although he never found any “lost tribes” of Jews. Like his namesake Benjamin of Tudela, JJ recorded the wide variety of Jewish practice and culture, including an extensive description of the Jewish community in Persia and the persecution they suffered as minorities in a Muslim country.

JJ’s last big trip was to America and his fascinating account of his experiences there from 1859 to 1862 provides the only extensive first-hand description of Jewish life in America before 1870. JJ’s observations about American Jews contained perceptive insights about the community’s character and future.

JJ was concerned about the direction of Jewish life in America. He felt that too much emphasis was placed on outside appearances, and not enough on spirituality. He counted 200 Orthodox congregations and only eight Reform, but the momentum was with the Reform movement and traditional Judaism seemed to be withering. To attract new congregants, Orthodox synagogues were building magnificent sanctuaries even as less and less Jews were seriously engaged with Jewish life. The Jews of America gave generously to charitable causes, an admirable trait, but JJ was concerned that they didn’t support Jewish education to the same degree. “Religious instruction in Jewish schools does not yet flourish as desired,” he said. “The learned Orthodox rabbis are very poorly represented in all of America.”

His respect for Jewish tradition landed JJ in hot water during a visit to New Orleans, according to Yated Neeman’s Jewish history blog. JJ Benjamin was a professional traveler, meaning that he made his livelihood through lectures, pre-sales of his books, and community support. When he reached New Orleans, his reputation as a raconteur and author had preceded him, and a “Benjamin Society” had formed whose members pledged to donate $5 a year for three years to support his work. However, things did not go as JJ had planned. He wrote, “Thirty-five members were accepted immediately and paid their dues at once. The money was handed over to a member of the executive board and, for all I know, he may still have it. Not only was the money not received by me, but I have the loss of about eighteen dollars to complain of in this affair. I was billed for the announcements and for the hall in which the meeting was held.”

Why did the Jewish leaders of New Orleans mistreat him like this? JJ believed that his involvement in a local dispute that became national Jewish news explains it. During JJ’s visit to the Portuguese congregation Shaare Chesed, a congregant stood up with an announcement. The synagogue was planning to erect a statue honoring Judah Touro, the noted Jewish philanthropist who spent time in New Orleans and died in 1854, and donations were being solicited to fund the memorial. Touro was known for his great generosity in supporting Jewish and non-Jewish causes, and had donated $20,000 to found Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York. Like the congregants at Shaare Chesed, Touro was descended from Portuguese Jews who’d fled the Inquisition in the 16th century, and they wanted to commemorate this important Jewish figure.

JJ Benjamin did not approve. Bluntly, he let his hosts know how he felt about the plan. “Gentlemen!” he cried in his thick Romanian accent, “Although I am only passing through the city and therefore have no right to take the floor in community affairs, I see myself forced to express my views in this matter because this concerns our religion, and in such a case every Jew has the right to speak. When I was young, I spent much time in Jewish studies and have recently seen four continents and have learnt something at firsthand about millions of our fellow Jews. Nowhere did I see or find the statue of a Jew, because this is clearly against the principles of our holy religion.”

JJ was so concerned about the proposed statue that the next day he approached Shaare Chesed’s rabbi and demanded to know his thoughts about it. The rabbi told JJ he fully supported the memorial. JJ argued that it was against Jewish law, but the rabbi disagreed, saying simply, “I don’t see that at all.” JJ provided proofs from scripture that the monument was not kosher, but the rabbi dismissed them, saying “That was in ancient times. Now, however, we live in the 19th century.” JJ responded with clear frustration, “If the world were twice as old as it is, our Torah would still be the same!”

Shaare Chesed did not appreciate JJ’s unsolicited advice, and the congregation withdrew its pledge of $900 to support his travels for three years. News of the episode spread throughout the American Jewish world, with some defending the monument and others agreeing with JJ’s view of the matter. Finally New Orleans Jewish leaders wrote to the most prominent European rabbis of the day, asking for their permission to erect the statue. All of them opposed the project – but apparently their influence was weak because the statue committee insisted they were moving forward regardless. However, outside events intervened. JJ wrote, “At this time, the Civil War in America broke out and ‘the L-rd annulled their decision and made their purposes in vain.’ Although, because of this affair, I suffered much and had great losses, nevertheless I had the satisfaction of having acted according to my convictions and of having opposed not without success, a memorial so public, so enduring and – so unJewish.”

With the United States engaged in a brutal Civil War, JJ Benjamin returned to Europe and published a new book in 1863, “Three Years in America.” The book garnered quite a bit of attention from Europeans fascinated by their American cousins, and JJ was honored by the kings of Sweden and Hanover. Determined to continue his travels, he planned another visit to Asia and Africa, and went to London to raise money. However, JJ’s years of roaming the globe had ruined his health and he was unable to continue traveling. Sick and without a way to earn a living, JJ died penniless in London. His supporters organized a fundraiser to help his widow and daughter.

JJ Benjamin never did find the lost tribes, nor did he ever achieve financial security, but his fascinating travelogues provide our most accurate look at Jewish life around the world in the mid-19th century.

Get the best of Accidental Talmudist in your inbox: sign up for our monthly newsletter.