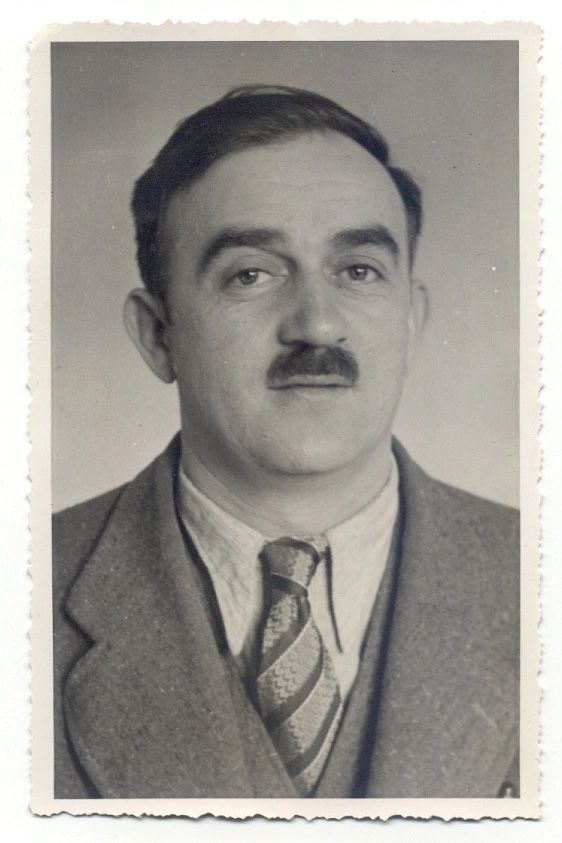

Anton Schmid was an Austrian electrician and devout Catholic who became a sergeant in the German army and used his position to help Jews in a variety of bold and ingenious ways.

Born in Vienna in 1900, Anton came from a humble background and was raised in the Roman Catholic church. After graduating from elementary school, he didn’t have the luxury of continuing his education but instead apprenticed as an electrician so he could help support his family. In 1918, Anton was drafted into the Austro-Hungarian Army and fought fiercely on the front lines in some of the final battles of World War I. After the war, Anton returned to Vienna, where he married a Catholic woman named Stefanie and had a daughter, Greta. He opened a small radio shop where he employed two Jews and lived a quiet life with his family. Nonpolitical and introverted, Anton tended to avoid conflict, until the German annexation of Austria in 1938, which led to increased persecution of Vienna’s Jewish population. Anton watched the rising hatred with alarm, and reached his limit when the home of his Jewish neighbor was viciously vandalized . Anton made a citizen’s arrest of the man responsible and then helped several desperate Jewish friends escape into Czechoslovakia. When war broke out in 1939 after Germany’s invasion of Poland, Anton was drafted into the German army as a sergeant at age 39 and sent to German-occupied Vilnius in Lithuania, where he was given a desk job due to his age. Anton’s military responsibilities included locating German soldiers who’d been separated from their units and reassigning them. He interrogated them and he took pity on many who’d gone AWOL due to combat fatigue, declining to charge them with desertion or cowardice, which would have resulted in execution.

In September 1941, 3700 Lithuanian Jews were rounded up and massacred in a pit outside of Vilnius. From his window, Anton had a view of the gathering point, and he was shocked and outraged by the ugly violence he witnessed. On that day Anton determined to do whatever he could to help Jews, no matter the danger to himself. The first Jew Anton helped was Max Salinger, a Polish Jew who was stateless and desperate. Anton gave him the identity papers of Private Max Huppert, a German soldier who’d been killed, and employed him as a typist in the military office, where Max worked until the end of the war. Anton next helped Luisa Emaitisaite, a young Jewish stenographer who was caught outside the ghetto after curfew and faced imminent death. Perhaps sensing something kind in his face, Luisa begged Anton for help and he hid her in his own apartment, then procured false identity papers for her and hired her as a stenographer. Like Max, Luisa survived the war due to Anton’s efforts.

Anton was just getting started. After the Germans occupied Lithuania, they impounded many businesses, and then needed workers to keep them running. In the beginning, facing a lack of skilled workers, the Germans were willing to employ Jews and provided them with work permits, which they called “leave from death papers” as they prevented the holders from deportation to concentration camps. However, in October 1941, killing Jews became top priority for the occupying German army, and they rescinded Jews’ work permits. Those working in Anton’s office begged him for help and he found an ingenious way to save them. He requisitioned military vehicles and festooned them with prominent signs warning of “dangerous explosives” inside. They passed through military checkpoints without being searched and the Nazis didn’t realized that the trucks were actually filled with Jews. Anton drove them to Lida, a nearby town where Jews were not yet being arrested. Anton also obtained valid “leave from death papers” and was able to employ 103 Jews in a variety of positions.

During this time, Anton hid Hermann Adler, a Jewish poet and resistance fighter, and his wife Anita, a well-known opera singer, in his small apartment. Through Hermann, Anton met other Jews active in the ghetto resistance and provided supplies that helped them commit acts of sabotage against the Nazi occupiers. Because of his ties to the Jewish resistance movement, Anton was arrested in January 1942 and imprisoned in an army jail. On February 25 he was sentenced to death. In his final letter to his family, Anton explained what motivated his heroic actions. “I want to tell you how this all came about. The Lithuanian military herded many Jews to a meadow outside of town and shot them, each time around two thousand to three thousand people. On their way they killed the children by hurling them against the trees, etc., you can imagine.” Perhaps Anton knew that the Nazis would one day deny what they’d done, and he wanted to leave a record of the atrocity. He told his family, “I have just acted as a human.” If only more people had acted like humans during that dark time.

Anton was executed by firing squad on April 13, 1942. Nobody knows how many Jews he saved, but the number is upwards of 250. In 1945, Hermann Adler published a collection of poetry in Switzerland, including the prose poem “Songs from the City of Death,” dedicated to Anton Schmid. Adler described Anton as “a socially awkward man in thought and speech” and a saintly figure. When Jews in the Vilna ghetto heard about Anton’s execution, they recited Kaddish, the Jewish mourners prayer.

After Anton’s death, his widow Stefanie was harassed by her neighbors, who smashed her windows and called her late husband a traitor. Anton was not acknowledged by Austria as a victim of the Nazis, so his families did not receive government support. When Max Tenenbaum, then in Israel, heard that Stefanie and Greta Schmid were living in poverty, he traveled to Vienna to tell them what Anton had done for him. From Israel, Max provided Stefanie and Greta with ongoing financial support, and publicized the story through his work as a journalist. In 1964, Israeli Holocaust Memorial Yad Vashem honored Anton Schmid as Righteous Among the Nations and brought his widow to Jerusalem to accept an award and plant a tree in her husband’s memory in the Garden of the Righteous. In 1965 the Simon Wiesenthal Center helped Stefanie travel to Vilna, where her husband was buried (Soviet regulations restricted movement), and erected a new gravestone with the inscription “Here Rests a Man Who Thought It Was More Important To Help His Fellow Man Than To Live.”

Abba Kovner, one of the few ghetto resistance fighters to survive, later testified at the trial of Adolf Eichmann, architect of the Nazis’ “Final Solution.” Kovner testified that the first time he heard of the unrepentant mass murderer was from Anton Schmid who told him of a rumor that “there is one dog called Eichmann and he arranges everything.” On the stand, he described Anton’s heroism: “During the few minutes it took Kovner to tell of the help that had come from a German sergeant, a hush settled over the courtroom; it was as though the crowd had spontaneously decided to observe the usual two minutes of silence in honor of the man named Anton Schmid. And in those two minutes, which were like a sudden burst of light in the midst of impenetrable, unfathomable darkness, a single thought stood out clearly, irrefutably, beyond question – how utterly different everything would be today in this courtroom, in Israel, in Germany, in all of Europe, and perhaps in all countries of the world, if only more such stories could have been told.” (Hannah Arendt)

Decades after his death, Anton was belatedly honored by Germany, which renamed a military base in his honor in 2000. At the ceremony, Minister of Defense Rudolf Scharping praised Anton Schmid as the model of a brave soldier, and German historian Wolfram Wette described Anton as “one of the gold grains under the heap of rubble” in Nazi Germany.

For saving the lives of hundreds of Jews at the cost of his own, we honor Anton Schmid as this week’s Thursday Hero.

Get the best of Accidental Talmudist in your inbox: sign up for our weekly newsletter.